Patient Education

Risk factors such as age, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, high blood cholesterol levels and family history can cause lipid (fatty) materials to clog these small diameter coronary arteries and form what are known as plaques (little humps of fatty material with some calcium deposits making them hard) on the inside lumen the artery. As the size of the plaque increases, the arteries start to narrow or stenose.

When one or more of these arteries get blocked the blood supply is reduced to the area of the heart muscle resulting in lack of nutrients and oxygen supply especially during exercise or exertion. This is often called "Coronary artery disease" (CAD) or "Atherosclerotic Heart disease".

Most people start experiencing chest pains or other symptoms like fatigue or shortness of breath when the block is over 50%. As the block gets narrower, symptoms increase either in intensity or frequency or both.

Heart attack or Myocardial Infarction occurs when the artery is completely occluded and the muscles die.

ECG, Treadmill, Echocardiogram will be done to diagnose CAD. Angiogram is done to show the accurate percentage of blocks in each artery.

1. Medical Management of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Initially Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) can be treated with tablets that can increase blood supply to the heart muscles either by dilating the blood vessels or making the heart pump the blood slowly but with more force. Aspirin or Anti-platelet therapy is given to keep the blood thin and prevent thrombosis. Medications are also given to reduce cholesterol/lipids levels in the blood and control diabetes and hypertension.

Angioplasty is an alternate invasive procedure to CABG, where the blocked arteries are opened up using a balloon catheter followed usually by metal ring like stent (resembles a coiled spring) to keep the opening from closing up again.

Patients with left main coronary artery stenosis or severe triple vessel disease (where all the 3 main coronary arteries have plaques) may not be eligible for a Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA).

Patients on high dose medications who continue to experience symptoms create a need for surgical intervention to remove or by-pass the blockages. In certain situation as described above the patient may not be fit for PTCA due to the nature of the disease and it is then that CABG is recommended.

2. Indications for Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG)

Indications for Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) depend on various factors, mainly on the individual's symptoms and severity of disease. Some of these include –

- Left main artery disease or equivalent

- Triple vessel disease

- Abnormal Left Ventricular function.

- Failed PTCA.

- Immediately after Myocardial Infarction (to help perfusion of the viable myocardium).

- Life threatening arrhythmias caused by a previous myocardial infarction.

- Occlusion of grafts from previous CABGs.

Bypass grafting may be contraindicated in patients, for e.g. absent viable myocardium or the artery that needs grafting is too small.

3. Before CABG Surgery

We encourage you to talk to your cardiologists and surgeons and discuss about the need and outcome of the surgery and at the same time understand its benefits and risks.

You should talk them about what medications can be taken on the day of the surgery, what pills need to be stopped and when. You will be hospitalized one or two days before the surgery giving enough time to have all the required pre-operative tests.

Laboratory tests (Blood and Urine analysis), Chest X-Ray, Electrocardiogram, Echocardiogram and breathing test (spirometry) will be done. Recent angiogram will always be required before having bypass surgery.

It is normal for all to be nervous and anxious before surgery. An anesthesiologist usually visits you the day before the procedure. He will discuss the plan and the postoperative pain management. He might prescribe an anti-anxiety medication as a part of the hospital's routine procedure. You will not be able to eat or drink anything from the evening or midnight before surgery. This is called "NPO" or nil per oral. You can take your medications with sips of water.

Prior to the procedure all personal belongings will be removed and handed over to your family member. Hair from chest and legs will be shaved off and you may be asked to shower with antiseptic soap to reduce the risk of infection. You will have Intravenous lines in one or both hands and one arterial line will be added in the operation room.

Inside the Operation Room

Once the anesthesia is administered a tube will be inserted into your windpipe through your mouth, which will be connected to a ventilator to assist your breathing. The general anesthesia helps you fall into deep sleep so that you feel no pain during surgery. The nurse then cleans the chest and the graft site (from where the vein or artery will be removed) with spirit and iodine. You will be completely covered with sterile drapes, exposing only the chest and the graft site (legs in case of vein graft).

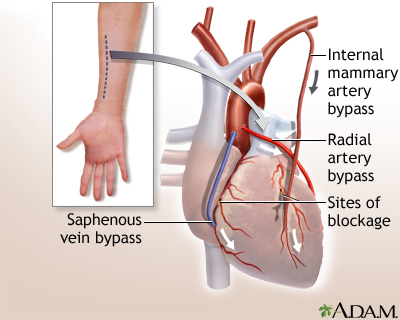

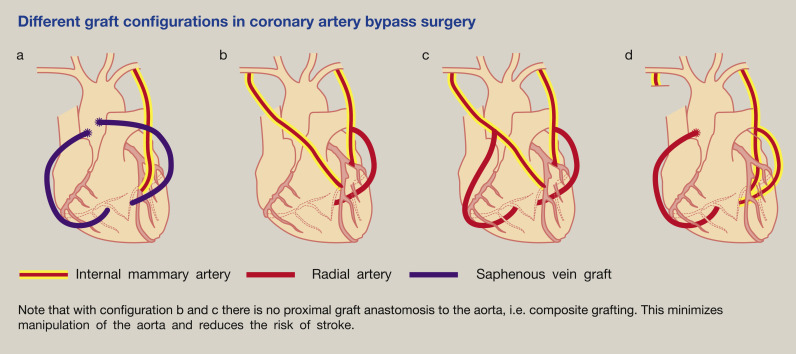

The number of grafts that you will need depends on the number of blockages or obstructions in the coronary arteries. One of the branches of the left main artery called as the "Left anterior descending" artery is usually grafted with an artery called "Left Internal Mammary artery". Another artery graft that can be used for CABG is the "Radial artery". The "ulnar artery" maintains the blood supply to the forearm when the radial artery is removed.

Artery supplying to the stomach "Gastroepiploic artery" and abdominal wall "Inferior epigastric artery" are less commonly used. However the most commonly used vessel is not an artery but a vein called the "Saphenous vein" from the thigh. This vein is usually removed from the groin to the knee or feet, in one or both legs depending on the number of grafts required.

4. Bypass Surgery Procedure

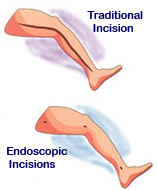

The surgeon or an assistant surgeon removes the graft from legs or hands, ensuring the other ends are ligated properly. He then cleans the unwanted fat and other tissues attached to the graft. Injects saline to ensure that all branches are properly ligated or clipped. Nowadays saphenous vein can be harvested with minimal incision to avoid scarring and delay in healing.

Meanwhile, the chest layers are cut open right in the middle almost on top of the sternum. When the sternum is reached, the bone is sawed and the ribcage is retracted to expose the heart.

ON pump CABG : The patient is connected to a heart lung machine by diverting blood from the systemic circulation through sterile plastic tubes.

The blood is oxygenized and filtered in the machine and sent back to the aorta thereby maintaining oxygen and nutrient supply to other vital organs. When the heart stops working, the surgeon identifies the block, makes incision (small cut) below the block. He then sutures the graft to that incision. Then the top end of the graft is sutured to the aorta. The left internal mammary artery that comes as a branch from aorta is left connected to its origin, however the distal or far end of the artery is divided for connection to the diseased coronary artery.

When all the grafts are in place and sutured, the heart is allowed to fill with blood and the heart lung machine is slowly weaned off. The surgeons make sure that there are no leaks in the connection between the graft and the aorta. Once the heart regains its function the pacing wires and drainage tubes are placed in the chest cavity to drain any fluid that normally collects after the procedure. The ribs are usually brought together and closed together with sternal wires and the rest of the muscles are closed in layers. The graft-harvested area is also sutured or closed in layers.

Following the surgery the chest wound is cleaned of the blood marks and dressed. The leg wound is dressed and bandaged with pressure to prevent swelling or limb edema.

Throughout the procedure an anesthesiologist will monitor the blood pressure, oxygen saturation and body temperature. Few blood tests may be repeated in intervals, especially when the patient is connected to the bypass machine.

Beating Heart Coronary Bypass Surgery(Off-pump CABG)

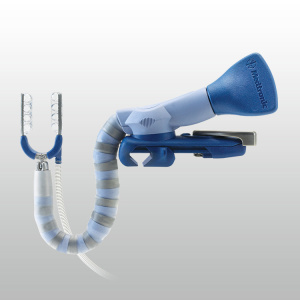

In many cases, coronary artery bypass grafting can be performed without the use of the heart-lung machine. In this "beating heart" (also called off-pump) technique, a small vertical incision is made in the chest, and a mechanical stabilizing device or a couple of interchangeable and complementary stabilizers called, The 'Octopus- evolution' and the 'Starfish' device are used to restrict movement of the heart so that the surgeon can perform surgery while the heart is beating. Patients may be given a drug to slow the heart rate, but the heart maintains its own rhythm without the assistance of the heart-lung machine. The potential benefits of off-pump surgery include a shorter hospital stay and recovery time, less bleeding, less potential for infection,reduced stroke rates and less trauma.

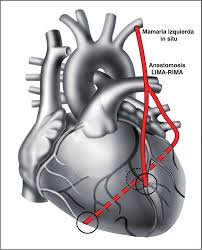

The other direct advantages would be faster ambulation, reduced ICU stay and 'no blood transfusion' in a majority of these patients. The choice of conduits continue to be the use of the universal 'Gold-standard', Left internal mammary artery bypass (LIMA ) to the Left anterior descending artery (LAD). The choice of the other conduits would be either it's companion, a pedicled RIMA , a free left or right radial artery ( depending on patient handedness ) and the standard reversed autologous reversed saphenous vein graft.

A beating heart CABG continues to be the new normal in CABG, the world over.

Our surgeons have a history of performing coronary artery bypass surgery achieving the highest levels of proficiency in the most commonly performed surgical procedure for treating coronary artery disease. We have achieved excellent outcomes: In the mortality rate among our CABG patients has been around 0.7 % for over a decade, year on year. These results are comparable to and sometimes exceed those at some of the best centers all over the globe.

We have special expertise in performing CABG in elderly patients (age 80 and older) and in those with co-existing medical conditions. Neither age nor other health conditions will restrict our ability to provide you with the best care to meet your individual needs.

During CABG, the surgeon removes a blood vessel from tissues of the chest, arms, or legs and uses it to route blood around blockages in the coronary arteries (the vessels supplying blood to the heart) to restore adequate blood circulation to the heart. We offer CABG through conventional open-heart and minimally invasive approaches.

With the minimally invasive approach, the surgeon makes a small (2-3 inch) incision between the ribs. This approach results in less chest trauma, less post-operative discomfort, shorter hospital stays, and a faster recovery time than traditional open CABG.We however insist on offering this procedure to only those who are good candidates for the procedure, only.

In most cases, CABG can be performed "off-pump" (without using the heart-lung machine). A stabilizer restricts heart movement so the surgeon can operate while the heart is beating. Patients may receive a drug to slow the heart rate, but the heart maintains its own rhythm without the assistance of the heart-lung machine. Off-pump surgery may shorten the hospital stay and recovery time and result in less bleeding, less potential for infection, and less trauma.

Different conduits :

LIMA RIMA Y (Total arterial CABG)

Saphenous Vein Incisions

After 1 month

5. Bypass Surgery Care

After the surgery you will be moved to the Intensive care unit and monitored closely. You will be still connected to the ventilator, until the anesthesia wears off and you start breathing on your own. Ventilator will be slowly weaned off in less than a day but this can take longer and varies from one case to another. You may still be able to communicate through hands and gestures. Nurses will have sign charts to ease the communication process. Chest tubes will be removed when drainage stops along with the pacing wires in about 1-2 days. Urinary catheter placed before the surgery will be used to measure your urinary output in the ICU and will be removed after a day or two.

Along with your regular medications, pain medications will be prescribed to alleviate the discomfort or pain in your chest where the incision has been made.

One or two members of your family will be allowed to visit you for a short while once or twice a day in the ICU. This however usually depends on the rules of the hospital. You can check this before surgery from the staff on the wards.

- Breathing exercises and cardio-pulmonary rehabilitation procedures will help in speedy recovery.

- You will be given liquid diets after the ventilator is removed, slowly progressing to solid foods.

- Sponge baths will be given and only when your incision is clean and dry, you can use soap and water to clean the chest.

- Changing positions in your bed helps you to recover quicker.

- A pillow is usually given to you to support your chest during coughing.

- Duration of Hospital stay purely depends upon the individual’s progress and may vary from a week or two.

6. Home Care Instructions

CABG does not cure the underlying disease, only creates an alternate pathway for the diseased arteries. When you leave the hospital, talk to your doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and dietitians about all the do and don'ts'.

On your discharge, you might have mixed feelings about leaving the hospital. Although you maybe anxious leaving the security of immediate medical care but you may at the same time be relieved thinking about your home and wanting to be back with relatives and friends. Complete recovery from surgery is a gradual process and you should take it one day at a time. These are some of the do's and don'ts -

- Wear comfortable clothes at all times.

- Take periodic walks and slowly increase the duration of exercise.

- Follow the diet prescribed by your dietician.

- Do not fail to take all your medications on time.

- Quit smoking.

- Participate in a cardiac rehabilitation program if possible.

- Maintain caution to avoid any bump or direct injury to your chest. Your scar might take one to two months to heal completely.

- Control your anger and stress.

- Follow up with your doctor(s) as instructed.

Some itching, numbness or redness in the incision site may be a normal process of healing. Contact the doctor immediately if there is a sign of infection (fever, pus or gaping of wound etc.).

you should take it one day at a time. These are some of the do's and don'ts -

7. Prognosis, Risks and Complications of Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

CABG has known to have significant improvements in the patients. Chest pain disappears in almost all of the patients, increasing the quality of life.

Studies have shown that only 3-4% of the patients come back in one year’s time with recurrent symptoms. Also 40% patients are symptom free for almost 10 years. The symptoms are usually of less intensity compared to before surgery. Also, the recurrence of chest pain is more in women than men.

When patients are in need of redo bypass surgery, the success rate is lower than for first operation.

Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery is a major surgical procedure and it carries some risks and complications. These complications are higher in patients who are heavy smokers or if they have a major problem with this other vital organs such as kidneys or lungs or have reduced blood supply to the brain.

Infection and bleeding are examples of risks and complications any surgery may present.

Some of these complications may be uncommon. Complications after surgery include-

- Ankle swelling

- Heart Attack

- Stroke

- Emboli

- Arrhythmias

- Vein graft occlusion

- Kidney failure or temporary shutdown

- Death

- Stress and Depression - could be long-term problem.

Some patients may lose some of their cognitive ability,especially older women, however most will regain it within six to 12 months. Usually bypass surgery will not cause dementia however it may worsen this condition if is is present prior to surgery.

The risk of death from CABG is approx 1%. The main reason of death is heart attacks occurring during or immediately after surgery. Heart attacks occurs in about 5% of the patients.

Neurological complications are minimal and occurs more in women than men, especially elder. Incidence of stroke is about 1-2 %.

Long term studies show that exercise reduces mortality rate by 20%.

8. Life style changes

'Healthy heart' after surgery

Prevention strategies can go a long way in improving the healthcare of a society. In India the increasing trend of heart disease is due to the increase in the incidence of hypertension and diabetes especially in the urban areas. Lifestyle that is applicable to maintain a 'healthy heart' is even more important after your surgery. Remember the following instructions to help your heart serve you better in the years following surgery -

"Don't eat your heart out". Eat healthy to avoid or control hypertension, weight, diabetes and cholesterol issues.

- Walk at least 30 minutes a day.

- Join a regular exercise program

- Quit smoking, avoid secondary smoke whenever possible.

- Reduce your stress level.

- Continue your medications as prescribed.

- Follow up with your doctor on a regular basis or immediately when symptoms recur.

- Discuss with your doctor about your work, if it includes manual labor.

9. FAQs

1. Who does Coronary artery bypass surgery?

A Cardiac Surgeon or a cardio-thoracic surgeon performs the surgery.

2. How long does the procedure last?

The procedure lasts about 3 to 6 hours; more time is required when there is more number of grafts.

3. What can I help my leg wound heal?

If you notice swelling in your feet or legs, keep your legs elevated using 2 or 3 pillows. Ankles should be higher than your knees and knees elevated than hips. This will allow the fluids to be reabsorbed and not form edema.

4. What is my role in staying healthy?

You should remember that there is no cure for Coronary artery surgery and life style changes are definitely required to prevent worsening of disease and staying healthy. Stop smoking; increase your exercise slowly and steadily, follow a well balanced diet and eat your medications regularly.

5. Are there any restrictions in the daily activities?

All normal activities can be done. Your doctor would specify your restrictions, which may include lifting moderate to heavy weights up to 3 months after surgery, limit climbing stairs in the first 2 weeks, sports until you are comfortable without symptoms and driving when you are still taking pain medications.

6. What should I do if my chest pain returns?

First of all, try to figure out if it is chest pain (angina) or pain in the incisional site. Angina will be usually similar to the pain prior to surgery and will increase or decrease with activity. Incisional pain will be a more constant pain and changes with position. If you are prescribed with Nitroglycerin, you can take that to relieve angina. If pain does not subside, you must go to a hospital’s emergency room as soon as possible or seek you doctor’s attention immediately

7. What is Minimally Invasive Technique for CABG?

Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB) surgery is an option for some patients who require a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) bypass graft to the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. Other minimally invasive surgery techniques include endoscopic or keyhole approaches (also called port access, thoracoscopic or video-assisted surgery) and robotic-assisted surgery.

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery include a smaller incision (3 to 4 inches instead of the 6- to 8-inch incision with traditional surgery) and smaller scars. Other possible benefits may include a reduced risk of infection, less bleeding, less pain and trauma, decreased length of stay in the hospital (3 to 5 days) and decreased recovery time.

The surgical team will carefully compare the advantages and disadvantages of minimally invasive CABG surgery versus traditional CABG surgery. Your surgeon will review the results of your diagnostic tests before your surgery.

BASICS OF HEART VALVES AND ITS SURGERY

This information you are viewing has been prepared for patients who may be facing a heart valve replacement or repair procedure. We are providing this information to help you and your loved ones learn more about the heart, how the heart valves function, how heart valve disease is diagnosed and the wide variety of treatment options available.

Please remember, this information is not intended to tell you everything you need to know about artificial heart valves or heart valve repair products, or about related medical care. Regular check-ups by a heart specialist are essential, and you are encouraged to call or see your doctor whenever you have questions or concerns about your health, especially if you experience any unusual symptoms or changes in your overall health.

What the heart does

The heart is a muscular organ located in the center of the chest between the lungs. Your heart is about the size of your two hands when they are clasped together. The heart is a sophisticated pump, providing blood flow to all of the cells, tissues and organs in your body. The right side of the heart pumps blood through the lungs, where the blood picks up oxygen and carbon dioxide is removed. The left side of the heart receives the oxygen-rich blood and pumps it to the rest of the body.

Inside your heart

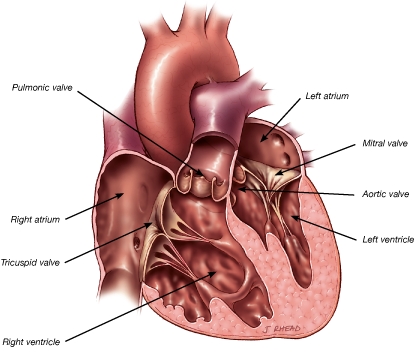

Chambers and valves of the heart

The heart contains four chambers. The heart pumps blood by contracting (squeezing blood out of its chambers) and relaxing (allowing blood to enter its chambers). The two upper chambers are called the atria. They receive blood returning from the body through veins. The two atria contract with only a small amount of force, sending the blood to the ventricles; the ventricles are the muscular, lower chambers of the heart. The ventricles contract with greater force, delivering blood to the body via your arteries. The right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs. Of all the chambers in the heart, the left ventricle does the greatest amount of work. Powerful contraction of the left ventricle sends oxygen-rich blood to all of the body’s organs.

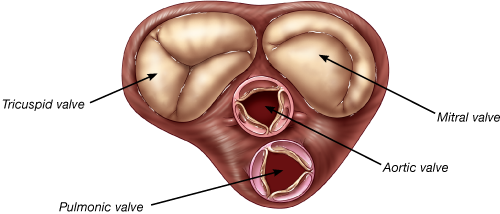

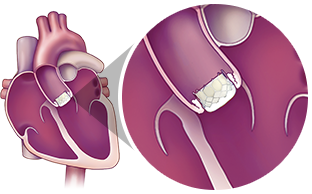

The heart also has four valves. Their purpose is to ensure that blood flows only in one direction. The heart’s valves open at the appropriate times to allow forward flow of blood, then close to prevent back-flow of blood. The mitral and tricuspid valves control the flow of blood from the atria to the ventricles. The aortic and pulmonic valves control the flow of blood out of the ventricles. The image below shows the chambers and valves of the heart.

Circulation through the body

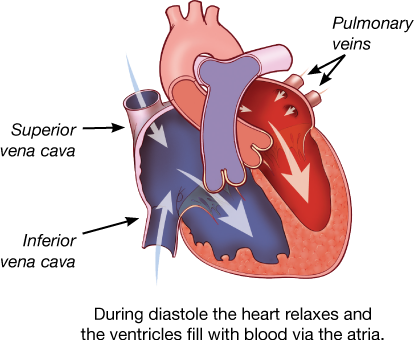

The purposes of blood are to deliver oxygen and nutrients to tissues and organs and to carry away waste products. There are actually two loops of circulation in the body.

The first is a circulation loop which goes from the heart to the lungs, where blood is mixed with oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is released. Carbon dioxide is a byproduct that the body makes when it uses oxygen. The other circulation loop goes to the body, where oxygen and other nutrients in the blood are exchanged for carbon dioxide and waste products produced by the body. Veins are the blood vessels which return blood to the heart. Arteries are the blood vessels which carry blood away from the heart to the lungs and the rest of the body.

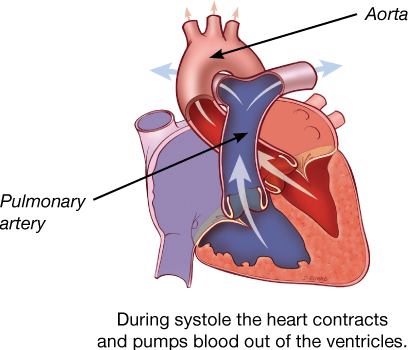

The heart muscle, the cardiac cycle and your blood pressure

The muscle of the heart (the myocardium) produces the forces necessary to eject (push) blood from the ventricles. When the ventricles contract, they force blood out of the heart through valves and into the aorta (from the left ventricle) or pulmonary artery (from the right ventricle). This phase of the heart cycle—when the ventricles are contracting and forcing blood from the heart— is called “systole."

After contracting, the ventricles must relax to receive the next volume of blood that needs to be pumped. When the ventricles relax, blood flows into them from the atria. This phase of the heart’s activity is called “diastole.’’

The combination of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole) is called the cardiac cycle. You may have encountered these terms when your blood pressure is measured from an artery in your arm. Your blood pressure measurement includes two numbers, which correspond to systole and diastole in your cardiac cycle. For example your blood pressure may be 120 over 80. 120 is your systolic blood pressure, representing the pressure generated by contraction of your left ventricle. 80 is called the diastolic blood pressure, and is the blood pressure in your body during the time when your left ventricle is relaxed and receiving blood.

The heart’s arteries

Like every other organ or muscle in the body, the heart has arteries that carry blood nutrients and oxygen. The heart’s arteries are called the coronary arteries. The three coronary arteries are the right coronary artery, the left anterior descending coronary artery, and the circumflex coronary artery. When these arteries become narrowed by build-up of cholesterol-containing plaque, a person is said to have coronary artery disease. If a coronary artery becomes completely blocked, a portion of the heart muscle is deprived of its blood supply, and a heart attack occurs. A heart attack causes damage to the heart muscle as some muscle cells die.

Normal, healthy heart valves

Human heart valves are remarkable structures. These tissue-paper thin flaps, or leaflets, attached to the heart wall undergo a constant “beating” as they open and close with each heart beat, day after day, and year after year. With each beat, the valves display their remarkable strength and flexibility.

There are four cardiac valves. Two of the valves are referred to as the atrioventricular (AV) valves. They control blood flow from the atria to the ventricles. The AV valve on the right side of the heart is called the tricuspid valve; it sits between the right atrium and the right ventricle. The name “tricuspid” refers to the three leaflets making up the valve. The AV valve on the left side of the heart is called the mitral valve; the mitral valve controls blood flow between the left atrium and left ventricle. It has two leaflets. The other two cardiac valves, i.e., the aortic and pulmonic valves, each have three leaflets. They are outflow valves, regulating the flow of blood as it leaves the ventricles and the heart. The aortic valve serves as the “door” between the heart and the rest of the body. Every drop of blood ejected by the left ventricle must pass through the aortic valve. The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and the ascending aorta, or upper portion of the aorta. The pulmonic valve is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. The mitral and tricuspid valves are substantially larger than the aortic and pulmonic valves.

The image below shows the shape and location of the four heart valves. The characteristic heart sounds (“lubb-dubb”) are caused by the closing of the heart valves; the first by closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves and the second by closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves.

Function of heart valves

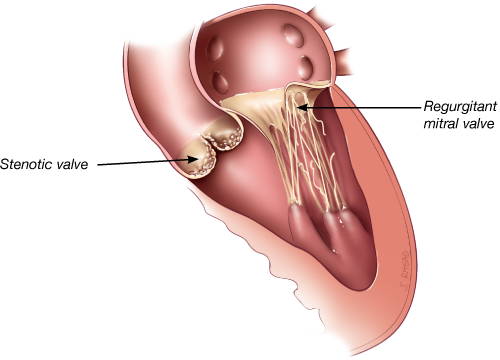

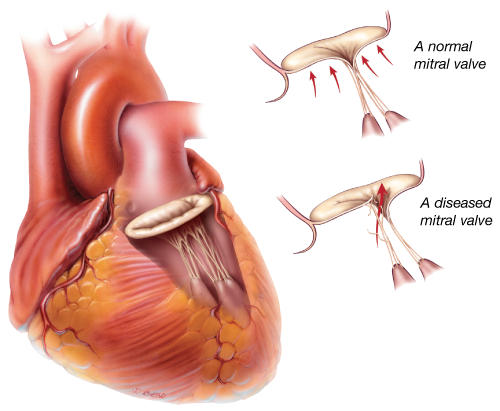

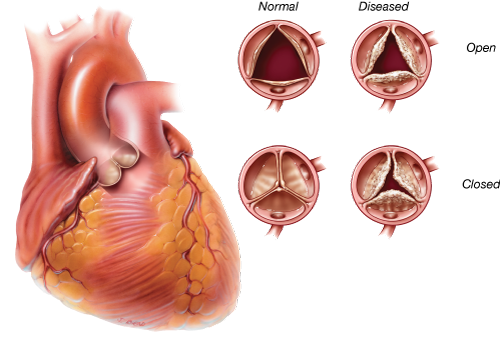

A normal, healthy valve would be one which minimizes obstruction and allows blood to flow freely in only one direction. It would close completely and quickly, not allowing much blood to flow back through the valve (backward flow of blood across a heart valve is called “regurgitation”). While a small amount of regurgitation, or leak, may be present and is well tolerated, severe regurgitation is always abnormal.

When a heart valve opens fully and evenly, blood flows through the valve in a smooth and even manner. When a valve does not open fully or evenly, blood flow through it becomes chaotic and turbulent. When a valve is narrowed or does not open fully, it is said to be “stenotic.”

Both regurgitation (a leak) and stenosis (a narrowing) increase the heart’s workload.

Valve defects and diagnosis

Valve defects and diagnosis

Heart valves can fail by becoming narrowed (stenotic) so that they block the flow of blood or leaky (regurgitant) so that blood flows backward in the heart. Sometimes a valve is both stenotic and regurgitant. A variety of conditions can cause these heart valve abnormalities.

Causes of heart valve disease

Degenerative valve disease – This is a common cause of valvular dysfunction. Most commonly affecting the mitral valve, it is a progressive process that represents slow degeneration from mitral valve prolapse (improper leaflet movement). Over time, the attachments of the valve thin out or rupture, and the leaflets become floppy and redundant. This leads to leakage through the valve.

Calcification due to aging – Calcification refers to the accumulation of calcium on the heart’s valves. The aortic valve is the most frequently affected. This build-up hardens and thickens the valve and can cause aortic stenosis, or narrowing of the aortic valve. As a result, the valve does not open completely, and blood flow is hindered. This blockage forces the heart to work harder and causes symptoms that include chest pain, reduced exercise capacity, shortness of breath and fainting spells. Calcification comes with age as calcium is deposited on the heart valve leaflets over the course of a lifetime. To learn more about aortic stenosis,

Coronary artery disease – Damage to the heart muscle as a result of a heart attack can affect function of the mitral valve. The mitral valve is attached to the left ventricle. If the left ventricle becomes enlarged after a heart attack, it can stretch the mitral valve and cause the valve to leak.

Rheumatic fever – Once a common cause of heart valve disease, rheumatic fever is now relatively rare in most developed countries. Rheumatic fever is caused by an infection of the Group A Streptococcus bacteria and can detrimentally affect the heart and cardiovascular system, especially the leaflet tissue of the valves. When rheumatic fever affects a heart valve, the valve may become stenotic, regurgitant or both. It is common for the heart valve abnormality to become apparent decades after the bout of rheumatic fever.

Congenital abnormalities – Congenital heart defects (present at birth) can affect the flow of blood through the cardiovascular system. Blood can flow in the wrong direction, in abnormal patterns, and can even be blocked, partially or completely, depending on the type of heart defect present. Ranging from mild defects such as a malformed valve to more severe problems like an entirely absent heart valve, congenital heart abnormalities require specialized treatments.

Bacterial endocarditis – Bacterial endocarditis is a bacterial infection that can affect the valves of the heart causing deformity and damage to the leaflets of the valve(s). This usually causes the valve to become regurgitant, or leaky, and is most commonly seen in the mitral valve.

Diagnosis of Valve Disease

Before a patient sees a primary care physician or a cardiologist (a doctor who specializes in understanding the heart) concerning a heart valve problem, he or she has often experienced some type of physical sign or discomfort. Some physical signs of heart valve disease include: angina (chest pain), tiredness, shortness of breath, lightheadedness or loss of consciousness.

However, in some cases a heart valve problem may cause no symptoms at all. These heart valve issues can often be identified by use of a stethoscope on routine physical examination. Heart valve abnormalities, whether stenosis or regurgitation, often produce a heart murmur. A heart murmur, particularly if it is new or loud, should prompt further investigation by your physician.

Cardiologists and surgeons have many ways of diagnosing heart valve disease. The most important is the echocardiogram.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a special application of ultrasound that enables the cardiologist to observe the function of your heart valves and the contractions of your heart muscle. During an echocardiogram, ultrasound waves are projected onto the heart. The reflected ultrasound is “captured” by a transducer, and a computer translates the sound waves into an image. Most echocardiograms are performed by placing the ultrasound probe on a person’s chest. This is called a “transthoracic” or “surface” echocardiogram. This test is non-invasive and takes only a few minutes.

In some cases, a tranesophageal echocardiogram is performed. With this type of echocardiogram, the ultrasound probe is inserted into the esophagus through the mouth. Because the esophagus is very close to the back of the heart, this sort of echocardiogram provides excellent images of the heart and its valves.

Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization (angiography) helps to determine the function of the coronary arteries and the heart valves. Cardiac catheterization is the process by which a tube is inserted into the blood vessels and/or heart. The tube injects a contrast medium (dye) which is then visualized with X-rays. Coronary angiography is particularly useful for analyzing the coronary vessels of the heart. Most patients have a coronary angiogram, or cardiac catheterization, before heart valve surgery; this is necessary to determine whether any blocked coronary arteries require treatment at the time of surgery.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray can be important in the detection of calcium deposits in the heart, such as on heart valves. It will also show the size and shape of the heart and lungs. All patients will have a chest X-ray before heart valve surgery.

Valve treatment

Diseased heart valves can be addressed in several ways. These include: 1) medication; 2) surgical valve repair; 3) surgical valve replacement; and 4) transcatheter valve replacement. While medication cannot correct valve dysfunction, it can alleviate symptoms in many cases. If repair or replacement becomes necessary, your cardiologist, surgeon or interventional cardiologist, will discuss the options with you. The choice between replacement or repair will depend on a number of factors, including the specific valve in question, the severity of the condition and whether the issue is stenosis or regurgitation.

Our heart team

If you will be undergoing a heart valve repair or replacement procedure, you will be cared for by a team of medical specialists who are committed to ensuring your safety and comfort before, during, and after, your procedure. Below you will find information describing different health care professionals you may meet during the course of your care.

Primary care physician — May be the first to identify the symptoms of heart valve disease or conditions that can cause heart valve disease or defects. He or she may order special tests to confirm the diagnosis or refer you to the appropriate specialist.

Cardiologist — A physician who specializes in diseases of the heart. The cardiologist does not perform heart surgery but often performs diagnostic studies to identify the cause of heart problems and determine the course of treatment to manage heart disease. The cardiologist may prescribe medications and/or refer you to a cardiovascular surgeon.

Cardiovascular surgeon — A physician who specializes in heart surgery, including the repair or replacement of diseased heart valves. The surgeon will help in the decision making process about timing and best course of action, including approach and device choice for your valve disease.

Interventional cardiologist — A physician who has additional specialized training to perform catheter-based procedures to treat heart diseases. The interventional cardiologist will work with the surgeon to determine the right candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacements.

Anesthesiologist — The anesthesiologist (doctor) or anesthetist (nurse) are trained to provide sedation or general anesthesia (sleep) during interventional procedures.

Critical care physicians and nurses — The critical care or intensive care unit is a specialized area in a hospital where you are closely monitored and treated after most interventional procedures. Working with your surgeon and/or cardiologist, the critical care team physicians and nurses manage your care during this time.

Surgical approaches for heart valve disease

Most heart surgery is performed through an incision across the full length of the breast bone, or sternum. This incision is called a median sternotomy. It generally heals quite well, with the bone requiring about 6 weeks for complete healing.

In selected patients, heart valve surgery can be performed using smaller, or minimally invasive, incisions. Smaller incisions may provide some benefit to patients. Preoperative studies, including a coronary angiography, echocardiography and, in many cases, chest CT (CAT) scan, help to determine which patients are candidates for minimally invasive surgery. These surgical approaches with small incisions also include use of the heart lung machine as do full sternotomy operations.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): A less invasive option to open heart surgery

For people who have been diagnosed with severe aortic stenosis, another option is available—transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). It is a less invasive procedure that does not require open heart surgery.

The TAVI procedure allows a new valve to be inserted with your diseased aortic valve. The new valve will push the leaflets of your diseased valve aside. The frame will use the leaflets of your diseased valve to anchor itself in place.

This less invasive procedure is different than open heart surgery. TAVI uses a catheter to deliver a replacement heart valve instead of opening the chest and completely removing the diseased valve.

The TAVI procedure can be performed through multiple approaches, how the most common approach is the transfemoral approach (through an incision in the leg). Only a Heart Team can decide which approach is best, based on a person's medical condition and other factors.

Please consult a Heart Team for more information on TAVI and its associated risks

Surgical valve replacement

If the cardiovascular surgeon chooses to replace the patient’s heart valve, the first step is to remove the diseased valve (excise the valve and calcium deposits) and then implant a prosthetic heart valve in its place. Prosthetic valves used to replace diseased natural valves are made from a variety of materials and come in a variety of sizes.

There are two broad categories of prosthetic heart valves that are used to replace diseased valves:

- Bioprosthetic or tissue valves made primarily from animal tissue [i.e., bovine (cow) pericardium (the tough sac surrounding its heart), a porcine (pig) aortic valve, or human valves taken from cadavers]

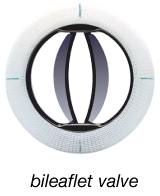

- Mechanical valves constructed from synthetic material, primarily carbon

Tissue valves (bioprosthetic valves)

There are a wide variety of tissue valves:

- Heterograft (or Xenograft) - valves or pericardial tissue harvested from medical-grade animals (i.e., bovine (cow) or porcine (pig))

- Homograft (or Allograft) - human valves taken from cadavers

- Autograft/Autologous tissue – normal valve that has been transferred from one position to another replacing a diseased valve within the same individual (confined to a pulmonic valve used to replace an aortic valve).

A heterograft is a biological valve made from animal tissue. For example, pericardial valves traditionally contain leaflets made from bovine (cow) pericardium (the sac surrounding its heart) and are sewn onto a flexible or semi-flexible frame. Another type of tissue valve is a porcine valve. A porcine valve is made from pig’s aortic heart valve and is usually sewn onto a flexible or semiflexible frame to make a “stented” valve; alternatively, the natural porcine aortic root is left intact to function as the frame to make a “stentless” valve.

Each valve is surrounded by a cloth sewing ring. Sutures are placed through this sewing ring to secure the valve to the heart.

Mechanical valves

Mechanical valves include leaflets that are made out of a special type of carbon. These valves usually have two leaflets. The leaflets open and close during the cardiac cycle, ensuring flow of blood in one direction.

Criteria and selection of heart valves

The choice between a mechanical and tissue valve depends upon an individual assessment of the benefits and risks of each valve and the lifestyle, age and medical condition of each patient.

Tissue valves do not require long-term use of blood thinners (anticoagulants). This is an important consideration for those who cannot take blood thinners because of a previous history of major bleeding (e.g., gastrointestinal or genitourinary) or an increased risk of traumatic injury and bleeding related to recreational activity, sports, or advanced age. Tissue valves generally last at least 10 years and, in some people, have lasted longer than 30 years. If a patient under 60 years of age receives a tissue valve, there is a high probability that he or she will require another valve replacement at some point; whereas, most patients who are 70 years and older do not.

Mechanical valves rarely wear out. However, they require daily treatment with blood thinners, and blood thinners can require changes in diet or activity levels.

The decision to choose a tissue or mechanical valve replacement is often related to the patient’s age, with older patients preferentially receiving tissue valves. However, there is no clear agreement on the precise age cutoff where a tissue valve may be preferable to a mechanical valve.

Valve repair

When possible, it is generally preferable to repair a patient’s valve rather than to replace it with a prosthetic device. Valve repair usually involves the surgeon modifying the tissue or underlying structures of the mitral or tricuspid valves.

Nearly all valve repairs include placement of an annuloplasty ring or band. This is a cloth-covered device that is implanted around the circumference, or annulus, of the mitral or tricuspid valve. It provides support to the patient’s own valve and brings the valve leaflets closer together, potentially reducing leaks across the valve. There are a variety of different annuloplasty devices. The surgeon will choose one that best fits your heart valve.

In addition to an annuloplasty, mitral valve repair frequently requires correction of problems with the leaflets or chords, which attach the valve leaflets to the heart. When a mitral valve leaks because of mitral valve prolapse, fixing the leaflets and chords (and adding an annuloplasty ring or band) restores normal valve function.

Care after a heart valve procedure

The normal recovery period from standard heart valve surgery requires four to eight weeks. Recovery may be faster when a smaller incision is employed, for example, with minimally invasive and transcatheter procedures. During this time, patients gradually gain energy and resume normal activities of daily living. Regular check-ups by a heart specialist are essential, and you are encouraged to call or see your doctor whenever you have questions or concerns about your health, especially if you experience any unusual symptoms or changes in your overall health.

Diet and exercise – Two additional important aspects of recovery and general wellness are maintenance of a healthful diet and regular exercise. If your doctor has recommended a special diet, it is important that it be followed. Healthy eating is an important part of a healthy life. During recovery, nutritious food gives your body energy and can help you heal more quickly.

To improve overall cardiovascular fitness, it is recommended that you combine a balanced diet with your doctor’s recommendations about exercise and weight control. Following a regular exercise program is an important part of maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Under your doctor’s guidance, you should gradually build up your exercise and activity level. Before you begin a new sports activity, check with your doctor.

Anticoagulants – It is important to follow your doctor’s directions for taking medications, especially if an anticoagulant has been prescribed. Anticoagulants, or blood thinners, decrease the blood’s natural ability to clot. If you must take anticoagulant drugs, you will need periodic blood tests to measure the blood’s ability to clot. This test result helps your doctor determine the amount of anticoagulant you need. It may take a while to establish the right dosage of this drug for you, but consistency and working with your doctor are important.

Home testing may also be available, so check with your physician about this option. Consult your doctor about interactions with any other drugs you may be taking and dietary restrictions you may have while taking anticoagulants, and also ask about any signs to watch for that might indicate your dosage is too high.

Other health information – Before any dental work, including teeth cleaning, endoscopy or surgery is done, tell your dentist or doctor about your prosthetic heart valve. Patients with a valve implant are more susceptible to infections that could lead to future heart damage. Therefore, it may be necessary to take antibiotics before and after certain medical procedures to reduce the risk of infection.

Furthermore, when traveling for more than a few days, try to maintain diet and exercise level as close to normal as possible. Be sure to discuss all your medicines (including over-the-counter medicines) with your doctor, and don’t change the dosage unless instructed to.

FAQs

1. What is a heart valve?

Your heart has four valves: the mitral valve and the aortic valve on the left side of your heart and the tricuspid valve and the pulmonic valve on the right side of your heart. In order for blood to move properly through your heart, each of these valves must open and close properly as the heart beats. The valves are composed of tissue (usually referred to as leaflets or cusps). This tissue comes together to close the valve, preventing blood from improperly mixing in the heart’s four chambers (right and left atrium and right and left ventricle).

2. When do the heart valves open and close?

You may notice that the beating of your heart makes a “lubb-dubb, lubb-dubb” sound. This sound corresponds to the opening and closing of the valves in your heart. The first “lubb” sound is softer than the second; this is the sound of the mitral and tricuspid valves closing after the ventricles have filled with blood. As the mitral and tricuspid valves close, the aortic and pulmonic valves open to allow blood to flow from the contracting ventricles. Blood from the left ventricle is pumped through the aortic valve to the rest of the body, while blood from the right ventricle goes through the pulmonic valve and on to the lungs. The second “dubb,” which is much louder, is the sound of the aortic and pulmonic valves closing.

3. How often do my heart valves open and close?

The average human heart beats 100,000 times per day. Over the life of an average 70-year-old, that means over 2.5 billion beats.

4. How big are my heart valves?

Your heart is about the size of your two hands clasped together. The aortic and pulmonic valves are about the size of a quarter or half dollar, while the mitral and tricuspid valves are about the size of an old-fashioned silver dollar.

5. What causes valvular heart disease?

There are several reasons that one or more of your heart valves may not work properly. The ultimate effect of a diseased heart valve is that it interrupts normal blood flow through the heart. Causes may include the following:

Endocarditis

– an infection of the valve tissue.

Rheumatic fever

– a specific type of infection more prevalent in developing countries where the valve tissue becomes inflamed and/or fused together.

Calcification

– over time, calcium in your body can build up on the tissue of your valves making it difficult for them to move properly.

Congenital defects

– a condition you are born with such as having only two leaflets on the aortic valve rather than three.

Ischemia

– also known as coronary artery disease, in which the heart’s own blood vessels become clogged and can no longer deliver the proper amount of blood.

Degenerative disease

– a progressive process that represents slow degeneration from mitral valve prolapse (improper leaflet movement). Over time, the attachments of the valve thin out or rupture and the leaflets become floppy and redundant.

6. How is valvular heart disease treated?

There are different methods for treating valvular heart disease, and you should discuss your options with your physician. In some cases, no action may be needed and a “wait and see” approach may be used. Your doctor may also prescribe various medications that may improve your symptoms. If the disease has progressed, your doctor may recommend intervention. What procedure is appropriate is a decision that your doctor will make in consultation with you. This is dependent upon such things as which valve or valves need to be addressed, your specific medical conditions, and other factors. In general, there are two options to treat valvular heart disease: one is to repair your native valve, and the other is to replace your native valve with a prosthetic valve.

7. What are my surgical options?

During typical “open-chest” surgery to repair or replace a heart valve, the surgeon makes one large main incision in the middle of the chest and breastbone to access the heart. A heart-lung machine takes over the job of circulating blood throughout the body during the procedure, because the heart must be still and quiet while the surgeon operates. Many surgeons are now able to offer their patients minimal incision valve surgery as an alternative to open-chest heart valve surgery. Smaller incisions may be on the side of the chest or in the center. In addition, for some patients it is possible to replace the aortic valve using less-invasive, catheter-based techniques. With these approaches, an interventional cardiologist guides a new valve or a repair device into the beating heart using guidance from X-ray and echocardiography. For example, a new valve may be inserted through an incision in the leg (or slightly higher up) that does not require the chest to be opened, and cardiopulmonary bypass or use of the heart-lung machine is usually not required.

8. How is minimal incision valve surgery performed?

Minimal incision valve surgery does not require a large incision or cutting through the entire breastbone. The surgeon gains access to the heart through smaller, less visible incisions (sometimes called “ports”) that are made between the ribs or a smaller breastbone incision. The diseased valve can be repaired or replaced with the surgeon looking at the heart directly or through a small, tube-shaped camera.

9. How can my heart valve be repaired?

In some cases, it is possible to repair your valve. Repair is most commonly performed on the mitral and tricuspid valves. The goal of the repair procedure is to fix your native valve so that it can open and close properly, thereby restoring normal blood flow through the heart. An implantable device which is usually ring-shaped with a metal core may be placed directly above your valve and tied in place with sutures. This procedure is called ring annuloplasty. The ring helps your valve maintain its proper shape so that blood does not leak out as the heart contracts and relaxes. This surgery can be performed with a conventional, full open-chest or through a less invasive or minimal incision approach as well.

10. How can my heart valve be replaced?

If your heart valve cannot be repaired, your doctor may decide to replace your native valve with a prosthetic valve. The aortic valve is the most commonly replaced heart valve. The prosthetic valves are usually one of two types: a mechanical valve or a tissue valve. A mechanical valve is made from synthetic (manmade) materials, primarily carbon. A tissue valve is usually made from either the tissue from a pig’s aorta or the tissue from the pericardium (sac surrounding the heart) of a cow. Valve replacement can be performed with a conventional, full open-chest or through less invasive or minimal incision approaches as well.

11. Are there any complications or other risks with heart valve surgery that I should know about?

Serious complications, sometimes leading to re-operation or death, may be associated with heart valve surgery. It is important to discuss your particular situation with your doctor to understand the possible risks, benefits, and complications associated with the surgery.

12. How long does an artificial heart valve last?

Longevity of an artificial tissue valve depends on many patient variables and medical conditions. This makes it impossible to predict how long a valve or repair device will last in any one patient. All patients with prosthetic heart valves should have a yearly echocardiogram and check-up in order to assess heart valve function.

13. Should I have a mechanical valve or a tissue valve?

You should discuss this question with your doctor as there are advantages and disadvantages to both. The key is to choose the valve that best fits your lifestyle and your goals. A mechanical valve may last longer than a tissue valve (which can wear out over time). However, patients with mechanical valves are required to be on anticoagulants (blood thinners) for life. Tissue valves do not require you to be on blood thinners for the rest of your life. However, they can wear out over time which may require a re-operation.

14. Should I expect an immediate improvement in my health following heart valve repair or replacement surgery?

The results of valve repair or replacement surgery vary for each individual. Many individuals feel relief from symptoms immediately, while other patients begin to notice an improvement in their symptoms in the weeks following surgery. Your doctor can help you to evaluate your progress and physical health following valve repair or replacement surgery.

15. How long after heart valve repair or replacement surgery can I resume “normal” levels of activity?

If you have a valve replaced or repaired, the normal recovery period is four to eight weeks, although minimally invasive approaches are often associated with more rapid recovery. Your ability to return to your normal daily activities depends on several factors, including the type of valve repair/replacement you’ve had, how you feel, how well your incision is healing, and the advice of your doctor. Regardless of the pace of your recovery, a supervised cardiac rehabilitation program is always helpful to regain energy and ensure overall good health.

16. Will I need to take any medications following my heart valve repair or replacement surgery?

As with any surgical procedure, you may be required to take medications following surgery. Discuss with your doctor which (if any) medications you may need, in particular if you received a mechanical valve which requires anticoagulants (blood thinners).

17. What do I need to know if I am required to take blood thinners after my surgery?

Anticoagulants, or blood thinners, decrease the blood’s natural ability to clot. If you must take anticoagulant drugs, you will need periodic blood tests to measure the blood’s ability to clot. This test result helps your doctor determine the amount of anticoagulant you need. It may take a while to establish the right dosage of this drug for you, but consistency and working with your doctor are important. Home testing may also be available, so check with your physician about this option. Consult your doctor about interactions with any other drugs you may be taking and dietary restrictions you may have while taking anticoagulants, and also ask about any signs to watch for that might indicate your dosage is too high.

18. How do I take care of my valve?

Be sure your dentist and doctors know that you have had heart valve surgery. Ask your dentist and doctor about taking antibiotics before dental or surgical procedures or endoscopy to help prevent valve infection. Always follow your doctor’s instructions carefully.

19. What happens when exposed to metal detectors, MRI or other electronic equipment?

Metals used in artificial valves are very small and do not set off an alarm in metal detectors. MRI, X-rays or any other electronic equipment do not cause any harm to the artificial valves.

20. Will mechanical valve make a noise?

Some patients say that they hear a clicking sound, while some patients don’t hear any sound; this varies from patient to patient. The person gets accustomed slowly to the sound and it’s nothing to worry about as it’s just the sound of the valve closing.

Preparing for Your Operation

Pre-operative Rehabilitation Recommendations

You will work together with your thoracic surgeon, nurses, and respiratory therapists, to achieve the best possible physical condition before your operation, to help you recover more easily and more quickly.

Smoking Cessation:

If you are still smoking, you must stop before your operation - at least two weeks, and if possible, four weeks.

If you need help with stopping smoking, please talk with your nurse, or your physician.

Aerobic Activity

- Walking is always good exercise. You should gradually strive to achieve walking a distance of at least 1 mile, twice daily, in less than 20 minutes. You may increase this to 2 miles as desired.

- Stair climbing also assists in improving circulation and breathing capacity. You could climb 2 flights of stairs, 4 times a day. The speed with which you climb these steps should gradually improve.

- If you are concerned about how to start this walking or stair climbing program, please discuss this with your nurse, or physician. If you have other medical problems, or a history of any cardiac problems, please discuss this with your physician.

Nutrition

- Eat a well-balanced diet

- Monitor your weight to make sure that it is staying in the range recommended by your doctor

Before your operation

Diet:

For the majority of surgeries we recommend no solid foods after midnight, the night before your operation. You may drink clear liquids until 4 hours prior to your operation.

Please be sure to discuss any special recommendations with your surgeon.

PAC

You will be evaluated by trained thoracic anesthetist and thoracic surgeon. Pre-operative necessary testing including labs , imaging, electrocardiogram , Echocardiography etc.

The Day of Surgery

Please remove any lipstick or nail polish on the day of your operation. Please leave all valuables and jewelry at home or with a family member.

Please arrive at the hospital at the designated time and check into the admissions desk. You will be taken to the pre-operative area, where you will change into a hospital gown. You will meet with an anesthesiologist and an intravenous (IV) line will be started.

When your operation is over your thoracic surgeon will speak with your family members. You will be taken to the recovery room when your operation is completed where you will be monitored until you are fully awake. If you go home after your procedure or operation, you will receive detailed instructions and additional contact information.

All other patients will be admitted to the hospital to the Thoracic Surgery Unit - with capacity for monitoring heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure and oxygen by experienced nurses and staff.

Recovery After Surgery

After your operation, you will be monitored to ensure your recovery is as smooth and comfortable as possible.

Pain Management

During your operation you may have a block performed or epidural placed to help with post-surgical pain management.

After surgery we use a combination of medications to treat the different components of pain including anti-inflammatories, nerve-specific medications, muscle relaxants and opioid pain medications.

Breathing Exercises

We will encourage you to perform deep breathing and coughing exercises to help keep your lungs expanded and to help bring up any mucus or sputum. You will be provided an Incentive Spirometer to help with deep breathing. The respiratory therapists and nursing staff will teach you how to use the Incentive Spirometer as well as how to brace your incision to help avoid pain while performing these important exercises.

Physical Activity

We will encourage you to start getting out of bed the day of surgery and begin walking the evening after surgery or the following morning. The nurses and physical therapist will help you to walk and assist with the lines and tubes or containers that you have. Walking is an essential part of recovery and we will encourage you to walk a minimum of 3 times daily while you are in the hospital.

Tubes and Equipment You May Encounter During Your Hospitalization

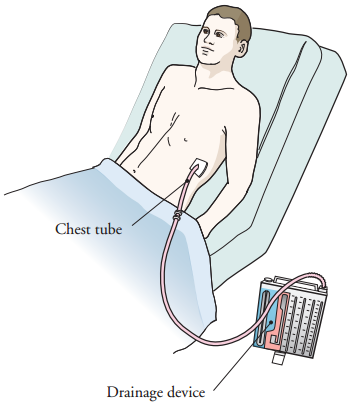

Chest Tube

A chest tube may be placed at the end of your operation. This tube drains air and blood which may collect around your lung after the operation. The chest tube is connected to a special collection container at the side of your bed. The nurse will measure the amount of fluid that drains into the container. Your surgeon will remove the tube when the lung has expanded and the air and fluid have stopped draining. The tube usually can be removed in 1-3 days after lung surgery and 5-7 days after esophagus surgery.

Cardiac Monitoring

Electrode pads will be put on your chest and attached to a heart monitor. This machine monitors your heart rate and rhythm and has an alarm that sounds on occasion. It is sensitive and on occasion, may make a sound even if the nurse touches you or if you move around in bed.

Intravenous (IV)/Arterial Line

You may have several IV lines. These are important for giving you fluids and medicines. The arterial line gives important information about your blood pressure, pulse, and amount of oxygen in your blood.

Foley Catheter

This tube drains urine from your bladder. It may be inserted after you go to sleep during your operation. The nurse measures the amount of urine you are making both during and after surgery. This is removed as soon as possible after surgery.

Prevention of Blood Clots

Blood clots, or deep venous thrombosis (DVT) can occur in the legs after any operation. If these blood clots form, they can break off and block off blood flow to the lung. This serious condition is called pulmonary embolism. Subcutaneous heparin and sequential compression stockings will be used to help prevent blood clots in the legs, and pulmonary embolism.

Discharge

When you are ready to be discharged from the hospital, your nurse will go over all the discharge instructions with you prior to leaving.

When to Call Your Thoracic Surgeon

Do not hesitate to call your surgeon for any problem that is of concern to you or your family. Generally, the common questions can be answered by one of our clinic nurses.

Call your surgeon if you have any of the following signs or symptoms:

- A large increase in mucus coughed up from your lungs.

- A change in the color of the mucus (for example, yellow, green, bright red).

- Difficulty breathing or new shortness of breath.

- A fever of 101.5 for more than 24 hours.

- Your incision becomes red or more painful.

Home Care Instructions

Physical Activity

Begin to resume normal physical activity as soon as possible after your operation. This helps to clear your lungs and helps the circulation in your legs. Begin with short walks gradually increasing your distance every day. Space activities throughout the day. To help the incision heal, don't lift objects weighing more than 10 lbs.; for example, a gallon of milk for up to 4 weeks after surgery.

Bathing

You make take a shower at home. Please avoid soaking in a tub or swimming before your incisions are fully healed.

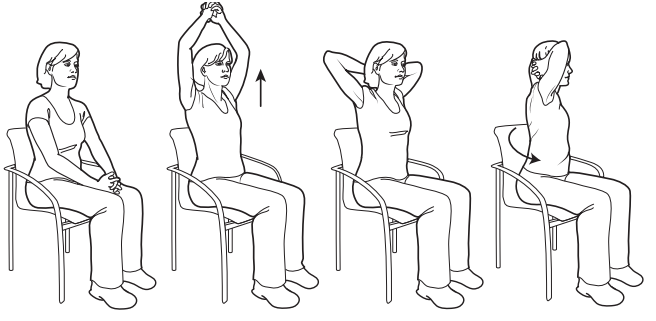

Breathing exercises

Deep breathing exercise should be continued at home so that your lungs will stay clear. The deep breathing exercises usually are most effective when you are sitting in a chair with your back well supported.

Nutrition

It is normal to lose your appetite for several days after an operation. However, good nutrition is important to help your body recover. Even if you are not hungry, try to eat at least half of each meal or small portions six times a day. Your appetite should return to near normal after a few weeks, especially as your activity increases. If your appetite is poor, try to eat high calorie and high protein foods such as shakes.

Constipation is a common problem after surgery, usually caused by the pain medicines. Drinking plenty of fluids and eating fresh fruit or bran will help prevent this problem. A stool softener may be ordered for you by your doctor. Please tell your doctor if this becomes a problem.

Medications

It is not unusual to have increased pain the first few days you are home and as you increase your activity. You may have pain in your incision for several weeks after your operation, and you will be given pain medicine to take at home. Do NOT take pain medicine before driving or with alcohol.

By 6 to 8 weeks after your operation, most of the pain in your incisions will be gone. You will also notice that the 'bump' along the incision will have flattened. It is normal for the area around your incision to feel numb for many months, and this will improve with time. This numbness may be worse on cold or damp days. Your pain will slowly decrease as healing occurs.

Wound Care

Tightness, itching, numbness or tingling around the incision area are often normal. These feelings may last for about 6 to 12 weeks, or longer.

Commonly Asked Questions: During Your Hospital Stay

1. Will I have pain after my surgery?

You will have some pain after your surgery. Your doctor and nurse will ask you about your pain often and give you medication as needed. If your pain isn’t relieved, tell your doctor or nurse. It’s important to control your pain so you can cough, breathe deeply, use your incentive spirometer, and get out of bed and walk.

You may get a prescription for pain medication before you leave the hospital. Talk with your doctor or nurse about possible side effects and when you should start switching to over-the-counter pain medications.

Pain medication may cause constipation (having fewer bowel movements than what’s normal for you). For more information, read the “How can I prevent constipation?” section below.

2. What is a chest tube?

Figure 1. Your chest tube and drainage device

A chest tube is a flexible tube that drains blood, fluid, and air from around your lung after surgery. The tube enters your body between your ribs and goes into the space between your chest wall and lung (see Figure 1).

3. When will my chest tube be removed?

Your chest tube will be removed when your lung is no longer leaking air and the drainage from your tube has decreased enough. Usually, this is when there’s less than 350 cubic centimeters (cc) of drainage per 24 hours.

After the tube is removed, the area will be covered with a bandage. Keep the bandage on for at least 48 hours, unless your nurse gives you other instructions.

Most people go home the same day that their chest tube is removed. Sometimes, your doctor may want you to stay in the hospital for another day after your chest tube is removed.

Look at your incisions with your nurse before you leave the hospital. This will help you notice any changes once you’re at home.

4. Why is it important to walk?

Walking helps prevent blood clots in your legs. It also lowers your risk of having other complications such as pneumonia. Walking 1 mile each day, which is 14 laps around the unit while you’re still in the hospital, is a good goal.

5. Will I be able to eat?

You will gradually start eating your normal diet again when you’re ready. Your doctor or nurse will give you more information.

6. When can I have visitors?

You can have visitors between 8:00 AM and 10:00 PM every day.

7. When will I leave the hospital?

How long you stay in the hospital depends on many things, such as the type of surgery you had and how you’re recovering. You will stay in the hospital until your doctor feels you’re ready to go home. Your nurse or doctor will tell you what day and time you can expect to be discharged.

Your doctor will talk with you if you need to stay in the hospital longer than planned. Examples of things that can cause you to stay in the hospital longer include:

- Air leaking from your lung

- Having an irregular heart rate

- Having problems with your breathing

- Having a temperature of 101° F (38.3° C) or higher

Commonly Asked Questions: At Home

1. Will I have pain when I am home?

The length of time each person has pain or discomfort varies. You may still have some pain when you go home and will probably be taking pain medication. Some people may have soreness around their incision, tightness, or muscle aches for 6 months or longer. This doesn’t mean that something is wrong. Follow the guidelines below.

- Take your medications as directed and as needed.

- Call your doctor if the medication prescribed for you doesn’t relieve your pain.

- Don’t drive or drink alcohol while you’re taking prescription pain medication.

- As your incisions heal, you will have less pain and need less pain medication. A mild pain reliever such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or ibuprofen (Advil®) will relieve aches and discomfort.

- Don’t stop taking your pain medication suddenly. Follow your doctor or nurse’s instructions for stopping.

- Don’t take more acetaminophen than the amount directed on the bottle or as instructed by your doctor or nurse. Taking too much acetaminophen can harm your liver.

- Pain medication should help you resume your normal activities. Take enough medication to do your exercises comfortably. However, it’s normal for your pain to increase slightly as you increase your level of activity.

- Keep track of when you take your pain medication. Pain medication is most effective 30 to 45 minutes after taking it. Taking it when your pain first begins is more effective than waiting for the pain to get worse.

Do the stretching exercises described in the “What exercises can I do?” section below. These will help to relieve the pain on the side of your surgery.

Pain medication may cause constipation (having fewer bowel movements than what’s normal for you). For more information, read the “How can I prevent constipation?” section below.

2. How do I care for my incisions?

You will have more than 1 incision after your surgery. The location of your incisions will depend on the type of surgery you had. There will be incisions from the surgical site and the chest tube. You may have some numbness below and in front of your incisions. You may also have some tingling and increased sensitivity around your incisions as they heal.

Surgical incision(s)

- By the time you’re ready to leave the hospital, your surgical incision(s) will have started to heal.

- Look at your incision(s) with your nurse before you leave the hospital so you know what it looks like. This will help you know if there are any changes later.

- If any fluid is draining from your incision(s), write down the amount, color, and if it has a smell.

- If you go home with Steri-Strips™ or Dermabond® on your incisions, they will loosen and fall off on their own. If they haven’t fallen off within 10 days, you can gently remove them.

Chest tube incision

- You may have some thin, yellow or pink-colored drainage from your incision. This is normal.

- Keep your incision covered with a bandage for 48 hours after your chest tube is removed, unless the bandage gets wet. If it gets wet, change the bandage as soon as possible.

- After 48 hours, if you don’t have any drainage, you can remove the bandage and keep your incision uncovered.

- If you have drainage, keep wearing a bandage until the drainage stops. Change it at least once a day or more often if the bandage becomes wet.

- Sometimes, the drainage may start again after it has stopped. This is normal. If this happens, cover the area with a bandage. Call your doctor’s office if you have questions.

3. Can I shower?

You can shower 48 hours after your chest tube is removed. Taking a warm shower is relaxing and can help decrease muscle aches. Remove your bandages and use soap to gently wash your incisions. Pat the areas dry with a towel after showering, and leave your incisions uncovered (unless there is drainage).

Don’t take tub baths until you discuss it with your doctor at the first appointment after your surgery.

4. What should I eat at home?

Eating a balanced diet high in protein will help you heal after surgery. Your diet should include a healthy protein source at each meal, as well as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. If you have questions about your diet, ask to see a dietitian.

5. How can I prevent constipation?

Your usual bowel pattern will change after surgery. You may have trouble passing stool (feces). Talk with your nurse about how to manage constipation.

- Drink 8 (8-ounce) glasses (2 liters) of liquids daily, if you can. Drink water, juices, soups, ice cream shakes, and other drinks that don’t have caffeine. Drinks with caffeine, such as coffee and soda, pull fluid out of the body.

- Both over-the-counter and prescription medications are available to treat constipation. Start with 1 of the following over-the-counter medications first:

- Docusate sodium (Colace®) 100 mg. Take 3 capsules once a day. This is a stool softener that causes few side effects. Don’t take it with mineral oil.

- Senna (Senokot®) 2 tablets at bedtime. This is a stimulant laxative, which can cause cramping.

- If you feel bloated, avoid foods that can cause gas, such as beans, broccoli, onions, cabbage, and cauliflower.

- If you haven’t had a bowel movement in 2 days, call your doctor or nurse.

6. How can I help my recovery?

- Exercise for at least 30 minutes each day. This will help you get stronger, feel better, and heal. Make a daily walk part of your routine.

- Keep using your incentive spirometer and do your coughing and deep breathing exercises at home.

- Drink liquids to help keep your mucus thin and easy to cough up. Ask your doctor how much you should drink each day. For most people, this will be at least 8 to 10 (8-ounce) glasses of water or other liquids (such as juices) each day.

- Use a humidifier in your bedroom during the winter months. Follow the directions for cleaning the machine. Change the water often.

- Avoid contact with people with colds, sore throats, or the flu. These things can cause infection.

- Do not drink alcohol, especially while you are taking pain medication.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking cigarettes is harmful to your health at any time. It is even more so as you’re healing after your surgery. Smoking causes the blood vessels in your body to become narrow. This decreases the amount of oxygen that reaches your wounds as they’re healing. Smoking can also cause problems with breathing and regular activities.

It’s also important to avoid places that are smoky. Your nurse can give you information to help you deal with other smokers or situations where smoke is present.

7. Can I resume my activities?

It’s important for you to resume your activities after surgery. Spread them out over the course of the day.

- Walking and stair climbing are excellent forms of exercise. Gradually increase the distance you walk. Climb stairs slowly, resting or stopping as needed.

- Do light household tasks. Try dusting, washing dishes, preparing light meals, and other activities as you’re able.

- Use the arm and shoulder on the side of your surgery in all of your activities. For example, use them when you bathe, brush your hair, and reach up to a cabinet shelf. This will help restore full use of your arm and shoulder.

- You may return to your usual sexual activity as soon as your incisions are well healed and you can do so without pain or fatigue.

Your body is an excellent guide for telling you when you have done too much. When you increase your activity, monitor your body’s reaction. You may find that you have more energy in the morning or the afternoon. Plan your activities for times of the day when you have more energy.

8. Is it normal to feel tired after surgery?

It’s common to have less energy than usual after your surgery. Recovery time is different for everyone. Increase your activities each day as much as you can. Always balance activity periods with rest periods. Rest is a vital part of your recovery.

It may take some time until your normal sleep pattern returns. Try not to nap during the day. Taking a shower before bed and taking your prescribed pain medications can also help.

9. When is it safe for me to drive?

You can begin driving again after you have:

- Regained full movement of the arm and shoulder on the side of your surgery

- Stopped taking narcotic pain medication (pain medication that may make you drowsy) for 24 hours.

10. Can I travel by plane?

Don’t travel by plane until your doctor says it’s okay. You will talk about this during your first appointment after your surgery.

11. When can I go back to work?